What Is PAM?

Table of Contents

The last post I did was the start of the Comprehensive Guide To AppArmor which took a look at the basics an administrator or developer needs to know to start creating and deploying AppArmor profiles for a program.

In the post I also left a question for the reader regarding AppArmor being used to replace the traditional DAC permissions (but never should!) and how you could use it to remove access to a file from a specific user (rather than a program).

However, this requires usage of the pam_apparmor module for PAM and due to this, before going into depth with using pam_apparmor, you should make sure you have a grasp of the basics of PAM and its configuration files.

This post was originally posted on August 7th 2016. Things may have changed since then, and this post may no longer be accurate. Proceed with caution.

Seriously What Is PAM? #

PAM stands for Pluggable Authentication Modules and is used to perform various types of tasks involving authentication, authorization and some modification (for example password change). It allows the system administrator to separate the details of authentication tasks from the applications themselves. This allows the policy to not only be generic, it means that the programs do not need to be modified in order to update the policy! An example of PAM usage is controlling login attempts to a shell/GUI interface so that only successful authentication and authorized events are allowed. You could also use PAM to control who can use the su binary to switch identities or control who can use the passwd utility to change passwords.

Overview #

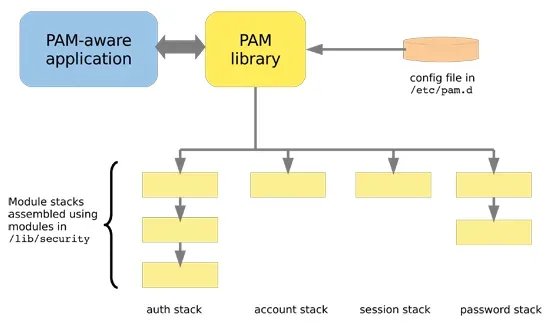

When a developer wishes to interact with PAM to let it handle events, they must include libpam which allows communication via the API provided by the library. When PAM sees a new event that it must process, it will look at the relevant configuration files found in /etc/pam.d and determine which modules must be used at certain stages.

PAM is capable of using context to determine what it needs to do, for example the pam_unix.so module has capabilities for the auth and account stack.

In the auth stack it checks a username and password combo while in the account stack it will check a users aging and expiration info.

This versatility is one of the reasons PAM has been so popular in the UNIX world, it allows for solutions that can be combined to create a generic library to deal with certain type of request.

How Do I Tell A Program Supports PAM? #

This is usually pretty easy, you can use ldd to check if libpam is in use:

comp:/home # ldd /usr/sbin/sshd | grep pam

libpam.so.0 => /lib64/libpam.so.0 (0x02209ddace0105400)

comp:/home # ldd /bin/su | grep pam

libpam.so.0 => /lib64/libpam.so.0 (0x02999ddace0105400)

libpam_misc.so.0 => /lib64/libpam_misc.so.0 (0x12211ddace1105400)

Configuration #

As I already mentioned, PAM configuration files are stored in /etc/pam.d for all valid programs.

A line in a configuration file will look something like this:

auth sufficient pam_rootok.so

There are three parts to this line, the first is called the function type which is the PAM function (stack) that an application asks PAM to perform.

The second is a control argument which is used to determine how PAM responds to a success or fail when performing the action.

The final part is the module which PAM calls when it reaches this line, it will determine what PAM specifically does to validate the auth attempt.

Function Types #

There are four possible functions that can be called inside a configuration file. Each of these provides a unique context that can be used within the module.

| Function Type | Description |

|---|---|

| auth | Authenticate a user, make sure they are who they say they are |

| account | Check user account status, ensure they are authorized to do action |

| session | Perform something for the users session like allocate resources they might need, for example mounting their home directory or setting usage limits |

| password | Change a users password or other creds |

Control Arguments #

Understanding control arguments is a critical part of creating a secure PAM policy, if you mess up the order you pay the price! There are five types of simple control arguments:

| Argument | Description |

|---|---|

| sufficient | if it succeeds then auth is successful and PAM does not need to look at more rules (assuming no required module failed), if it fails then keep going |

| requisite | if it succeeds PAM proceeds to additional rules, if it fails then PAM stops and sends a failure message |

| required | if it succeeds then proceed to next line, if it fails then proceeds to additional rules but will always return an unsuccessful auth regardless of end result. Useful because it will not say what caused the failure, thus an attacker will not be able to know if they got some part of the auth right |

| optional | the result is ignored, only becomes necessary for successful auth when no other modules reference the function |

| include | pulls in all lines in the config file which match the given param and appends them as arguments to the module |

Module Arguments #

PAM is also capable of taking arguments and passing them to the target module. This allows an administrator to specify constraints like min/max length for passwords or if a module should run in debug mode. The following is an example of how you can pass arguments to a module:

auth sufficient pam_unix.so nullok

As you can see all you need to do is append the line with the values you wish to pass to the module. In this case the value nullok tells pam_unix that it is okay to be supplied no password at all by the user. In the case you wish to pass more than one argument to the module you can simply separate them using spaces like so:

session optional pam_apparmor.so order=user,group,default debug

Simple Example #

Now that you know what the contents of a PAM file mean, lets look at a simple example from the book How Linux Works (2nd Edition) by Brian Ward. The following is a PAM config (albiet old) for the chsh utility:

auth sufficient pam_rootok.so

auth requisite pam_shells.so

auth sufficient pam_unix.so

auth required pam_deny.so

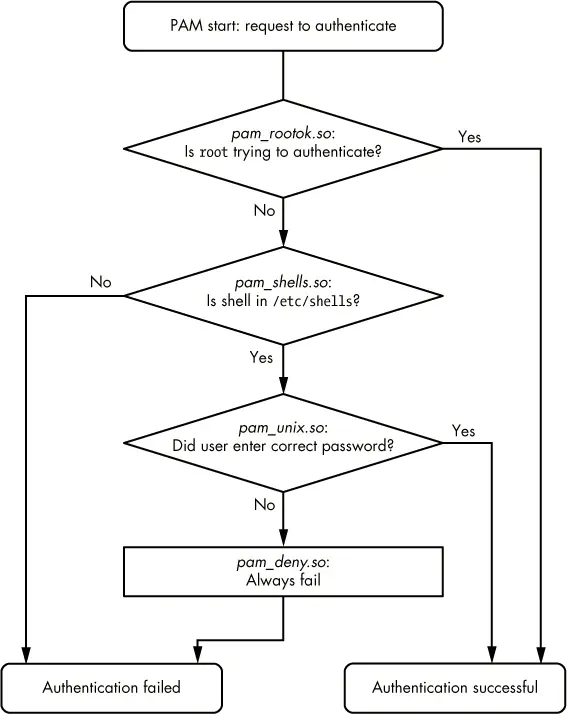

The first line says that if the user attempting the action is root then that is enough authority for PAM, and it will consider the authentication successful and end. If the user is not root then PAM will continue to the next line.

The second line checks to see if the shell the user is attempting to switch to is listed in /etc/shells. If it is not listed there then PAM considers this an authentication failure and immediately quits. It will also output an error message stating why the failure occured. If the shell is listed in /etc/shells then PAM continues to the next line.

The third line attempts to authenticate a user via their password. If the user provides the correct password then PAM will consider the authentication successful and end. If however the password is wrong, then PAM will continue to the fourth and final line.

The fourth line in this sample file may look the same as all the rest, but it is actually special. The pam_deny module is what can be called a default deny module, it will always return an authentication failure no matter what function or control arguments call it. This is similar to the idea of how firewalls are configured with a default deny rule at the very end of the chain so that any packet which does not match a previous rule is dropped. In this case PAM will have an authentication failure and will not explain why it failed. This is a very important part of making PAM configs, make sure you have the default deny policy at the end and use the required control argument so that an adversary cannot tell what caused the failure.

In case it helps, the author was kind enough to provide a flow chart to illustrate how PAM will deal with this module:

Practice #

Here is another example of a PAM config file:

auth required pam_securetty.so

auth required pam_unix.so nullok

auth required pam_nologin.so

account required pam_unix.so

password required pam_cracklib.so retry=3

password required pam_unix.so shadow nullok use_authtok

session required pam_unix.so

Try and write out/draw what PAM will do for this file, don’t worry too much about what the modules that are called do but focus on what each function and control argument try to do. Once you think you have it done, continue reading.

So I hope you saw that since the config file above contains only the required control argument, if there is ever a failure with one of the modules the user will not know which specific step caused the failure. This can be useful is cases when we do not want the adversary to be able to tell which of their actions caused the failure, making it harder for them to tell what they did right and what they did wrong (for example if they guessed a password, path or ID correctly).

The Big Kahuna #

Let's look at a modern chsh config for PAM:

#%PAM-1.0

auth sufficient pam_rootok.so

auth include common-auth

account include common-account

password include common-password

session include common-session

Recall the function of the include control argument:

include — pulls in all lines in the config file which match the given param and appends them as arguments to the module

This means that once PAM has finished processing the include lines, the file ends up looking like this (only in memory, file on disk is not written to):

#%PAM-1.0

auth sufficient pam_rootok.so

# common-auth

auth required pam_env.so

auth optional pam_gnome_keyring.so

auth required pam_unix.so try_first_pass

# common-account

account required pam_unix.so try_first_pass

# common-password

password requisite pam_cracklib.so

password optional pam_gnome_keyring.so use_authtok

password required pam_unix.so use_authtok nullok shadow try_first_pass

# common-session

session required pam_limits.so

session required pam_unix.so try_first_pass

session optional pam_umask.so

session optional pam_systemd.so

session optional pam_gnome_keyring.so auto_start only_if=gdm,gdm-password,lxdm,lightdm

session optional pam_env.so

Just like the previous exercise, try and write out/draw what the flow of the PAM module will be given these modules. Remember that the required control argument only outputs a failure at the end of the run. This prevents the adversary from being able to know what step failed (no error message) and it prevents them from being able to perform a timing attack to attempt a guess at the failed step. If you are able to map out the flow of this module then you have a good grasp of PAM and should feel confident approaching any other modules on a modern Linux system!